Housing Command Centers: An Emergency Response to Homelessness

AUTHORS: Emily Desmond

Additional contributions from Emily Collins, Liam Haggerty, and Cole Chandler

Key Points

- Housing and Homelessness Command Centers apply disaster response and emergency management practices to quickly re-house individuals experiencing homelessness and connect them with needed supportive services.

- Cities as diverse as Houston, Denver, and Cleveland have successfully utilized this model.

- Through this model, communities have achieved “functional zero” homelessness, where the number of people exiting homelessness consistently exceeds the number entering homelessness.

Homelessness is a solvable problem when approached with sustained commitment and investment. In many communities, myriad organizations and departments are addressing various aspects of this complex, multi-faceted challenge. Insufficient coordination and inadequate resources to meet the scale and depth of the challenge have created a broken system. As a result, the re-housing process often moves too slowly or stalls completely, leaving over 274,000 people across the U.S. sleeping outside on any given night. Cities and local leaders are on the frontlines of this crisis, and they possess the capacity to bring people inside and provide them with tailored support to break the cycle of homelessness.

A Housing Command Center (HCC) is a model used by some localities to tackle this challenge; it applies many of the same disaster response and emergency management practices typically used to support large groups of people abruptly in need of housing. The HCC model enhances coordination between the key players – outreach workers, local government, private landlords, law enforcement, and social service providers – to address people’s specific needs and provide housing as quickly as possible. This tool outlines the steps to build an effective HCC that brings together disparate pieces of the housing and social services ecosystems, leverages existing resources, and organizes a focused emergency response to quickly re-house individuals experiencing homelessness and connect them with needed supportive services.

The Challenge This Tool Solves

In most communities, the process of accessing permanent housing once homeless is slow, difficult, and disjointed. Individuals and families experiencing homelessness may need to navigate numerous systems and organizations, all of which may have differing eligibility requirements. This can force those experiencing homelessness to waste valuable time navigating complex processes to qualify for aid, and they are still likely to end up on wait lists, especially when housing units may already be in short supply. A “Housing Command Center” or “Housing Central Command” enables people to be re-housed quickly in either transitional or permanent supportive housing through a defined workflow and intentional coordination. The process empowers outreach workers with the resources, in partnership with the city and housing providers, to match individuals or families with housing units that meet their bespoke needs. HCCs utilize a “Housing First” approach, prioritizing getting people into housing to enable a base level of stability before addressing other issues related to behavioral health, substance abuse, employment, or other challenges. By examining the homelessness response system comprehensively, HCC leadership can identify bottlenecks and roadblocks and map a smoother, more successful process that keeps all the interested parties around the table.

Types of Communities That Could Use This Tool

The core elements of this tool could benefit any community when appropriately tailored to local circumstances. An HCC can be most immediately impactful in places with large encampments as ideal implementation starts with concentrating resources, building trust with those experiencing homelessness, testing the system across a wide spectrum of needs, and quickly adjusting and iterating. In Denver and Cleveland, it was critical that the cities had “unit teams” able to find existing vacant units – whether in the private market or in temporary non-congregate shelter options such as hotels or micro communities – so that outreach works could provide housing options as part of their initial engagement with people living in encampments. Nearly every community, small or large, has a dedicated system of government and nonprofit organizations in their “Continuum of Care” for homelessness services; a Housing Command Center can work in all of these places by taking a more urgent, systems level approach to how a community organizes around and adapts to its homelessness needs.

Expected Impacts of This Tool

Through this model, communities can achieve “equilibrium” or “functional zero” homelessness, where the number of people exiting homelessness consistently exceeds the number entering homelessness. When people do experience homelessness it is short-term, making homelessness rare, brief, and nonrecurring.

Homelessness affects communities across the country, from urban to suburban to rural areas, and has worsened as the affordable housing supply has grown increasingly constrained. The number of individuals experiencing homelessness reached a record high in 2024, with an 18% increase over the previous record set in 2023. Continuum of Care representatives, who are part of the designated local or regional organization funded through HUD to lead the community- wide response to homelessness, cite the expiration of eviction moratoria and pandemic rental assistance, increased migration, and natural disasters (such as the Maui wildfires and Hurricane Helene) as significant contributing factors. HUD’s 2024 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report revealed that one in three individuals experiencing homelessness meets HUD’s definition of chronically homeless, reaching an all-time high in the chronically homeless population since data collection began.

The inflow of people entering homelessness shows little sign of slowing. The re-housing process is facing bottlenecks, with shelter systems unable to provide enough support despite continued increases in the number of shelter beds available. According to HUD’s System Performance Measures, the national average length of time homeless ranged from 156 days to 193 days between 2019 and 2023. In 2023, 18.7% of individuals or families who exited to permanent housing experienced subsequent returns to homelessness. The shortage of affordable rental housing continues to compound the homelessness crisis, and with shelter spaces in short supply or with eligibility restrictions that make them inaccessible for some, many people are forced into unsheltered homelessness or unsafe accommodations. Furthermore, funding remains a major challenge for local communities addressing homelessness. Only one in four eligible households receives a Housing Choice Voucher, while rising rental and construction costs have outpaced available resources, meaning that funding streams remain insufficient to address the entirety of the challenge. Furthermore, increasing the affordable housing supply alone would not solve homelessness, as many who experience homelessness require supportive services.

The recent Supreme Court case City of Grants Pass v. Gloria Johnson, which ruled that the City of Grants Pass had the authority to pass laws making it illegal to sleep outside, has elevated the challenges associated with unsheltered homelessness. In the wake of this decision, over 100 cities have criminalized people sleeping outside, even when they have nowhere else to go. These laws span rural, suburban, and urban areas across states from California to West Virginia. Criminalization of homelessness is increasing despite ample evidence that punitive approaches often cost more and prove less effective than providing housing and services to those experiencing homelessness.

As the nonprofit Community Solutions emphasizes, a major problem with current homelessness response strategies in many communities is that accountability is dispersed across numerous agencies and organizations—no single actor is fully accountable for solving homelessness. While Continuums of Care (CoC) have the formal responsibility of coordination and strategic planning for communities, organizations within a CoC often maintain siloes focused on their specific programs. This siloed ecosystem often lacks a clear objective — such as achieving functional zero homelessness. Additionally, the yearly Point-In-Time (PIT) count of people experiencing homelessness is not specific enough to enable targeted action given that the people experiencing homelessness differs each night. These challenges with organization, accountability, and data have led to a broken re-housing system that fails to outpace the inflow of people into homelessness.

Though federal government funding and HUD systems undergird the homelessness response, localities must take responsibility for implementing solutions within that federal system and their local context; this takes on heightened importance as of the writing of this tool there are threats to those federal funding sources. In recent years, mayors in Denver and Cleveland, among others, have campaigned on this issue, bringing necessary attention and prioritization to developing solutions, and have found success with the Housing Command Center model.

Housing Command Centers

The solution to homelessness seems simple: match people in need of support and shelter with services and available housing units. However, simple does not mean easy, and HCC implementation requires committed leadership and both initial funding for structural and systemic changes as well as sustained funding to maintain the new system. In terms of leadership, communities must identify the center of gravity for decision-making to drive a different type of response and organize resources differently to address homelessness. This center of gravity could be the mayor, the city manager, the business community, an outspoken advocate, a faith leader, or really anyone who has strong influence and reach in their community and the power to enact change in the response system. Prior to implementation, successful communities must also have homeless assistance providers with enough capacity to provide case management and re-housing, given that an HCC relies on outreach workers. It is also critical that there be a centralized team responsible for acquiring units under the HCC, rather than having this function distributed across multiple entities, as pairing housing options with outreach is critical to expediting the re-housing process.

Communities have used various funding methods for HCC responses to homelessness. Houston’s model relied on federal funding for specific challenges or disasters and leverages Housing Choice Vouchers. Recent examples have been able to rely less on federal funding. Cleveland primarily uses general operating budget funds combined with emergency vouchers allocated through the American Rescue Plan Act that needed to be used, while Denver funds its program through a retail sales tax increase specifically designated for funding homelessness services and housing. In both Cleveland and Denver, the average annual cost to house an individual and provide necessary supportive services ranges from $24,000 to $30,000.

Housing Command Centers represent a fundamental shift in how communities respond to homelessness by treating it as an urgent crisis and implementing a unified approach to accelerating housing placement. By leveraging its authority to establish shared goals and coordinate efforts among service providers and landlords, a city can lead a more streamlined, efficient re-housing process and connect unhoused people with individualized services they need. Modeling the urgency displayed in responding to natural disasters, HCC teams rapidly assess needs, match individuals to available housing and services, and remove barriers to placement, drastically reducing the time required to house individuals. By prioritizing collaboration, flexibility, and speed, HCCs ensure that people experiencing homelessness receive timely support. While specific funding sources and intervention points may vary by locality, the core principle remains the same: homelessness is an emergency and warrants the same level of urgency as any other disaster.

Irma, and Maria in 2017. The magnitude of these disasters created a need to rethink the local emergency housing response, with FEMA supporting the development and implementation of a new approach. When flooding struck Baton Rouge in 2016, there happened to be one person serving as the Executive Director of the Housing Authority, embedded within the Housing Finance Agency, and overseeing the Emergency Solutions Grant (ESG) program. This individual was therefore able to take more of a systems level approach to combine and streamline funding to better and more quickly meet housing needs. The overlap in roles enabled the state to respond to the floods using HOME Tenant Based Rental Assistance, ESG, and Housing Choice Vouchers so that people in disaster shelters could exit to permanent housing.

This streamlined approach to natural disaster response informed Houston’s recovery from Hurricane Harvey the following year, leveraging Category B of FEMA’s Public Assistance Program to implement a Command Center for housing. The Command Center adapted the latter hierarchy of emergency response to homelessness policy and interventions, enabling quick decision-making to house and serve people in need. Houston’s first Special Assistant to the Mayor for Homeless Initiatives, appointed in 2013, brought targeted focus to this issue and successfully led design and implementation of the HCC response. As of 2022, Houston was able to reduce the wait time for housing to 32 days, a remarkable reduction from the average of 720 days in 2012.

Today, Houston is widely regarded as a national leader in implementing a coordinated response to homelessness. The city’s first targeted response began prior to the hurricanes, with participation in the Mayors Challenge to End Veteran Homelessness in 2012. This challenge created the impetus and federal resources for then-Mayor Annise Parker to convene all relevant parties and figure out how to match HUD-VASH vouchers with veterans experiencing homelessness, resulting in “functional-zero” for veteran homelessness. The city then moved to partner with Harris County to combine the mental health services of the county and the housing funding services of the city to tackle broader homelessness using the same streamlined model. Since 2012, according to the Coalition for the Homeless of Houston / Harris County, over 33,000 people have been housed with a 90% success rate for local housing programs. This collaboration went a step further in the aftermath of the hurricanes in 2017, when Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner declared that no one would leave the disaster shelters homeless. This disaster brought additional federal resources, allowing Houston to treat broader homelessness with the urgency of an emergency response.

The COVID-19 pandemic further crystallized and expanded this “unified command group” response, especially given that providing non-congregate shelter options at this time became essential. Los Angeles launched Project Roomkey to provide hotel and motel rooms to individuals experiencing homelessness who were particularly vulnerable to COVID-19, and the State of California launched the Homekey program to provide funds to acquire and/or develop hotels and motels for conversion into permanent supportive housing. Through collaboration between the federal, state, and county governments as well as the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (LAHSA), 4,000 units in 37 hotels and motels were secured for temporary housing. The expedient response catalyzed by the COVID-19 emergency made leaders start to work through how this type of re-housing process could be extrapolated and sustained. On her first day in office in 2022, Mayor Karen Bass declared a State of Emergency on homelessness and launched Inside Safe, which has brought over 4,000 people inside and over 900 of them into permanent housing through a Command Center approach.

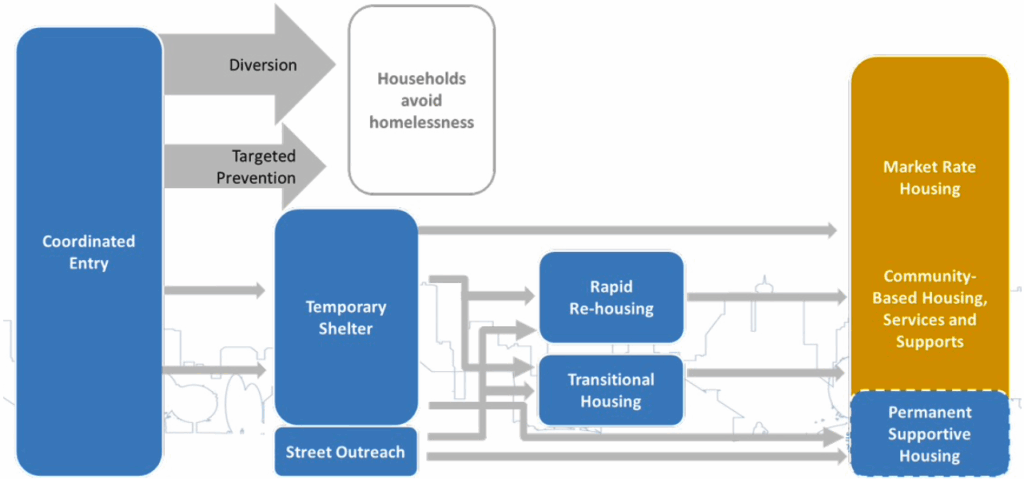

The following case studies examine two cities, Denver and Cleveland, that have achieved great success with the Housing Command Center approach, using it to accelerate the housing process at different intervention points. In Cleveland, a right-to-shelter city, the A Home for Every Neighbor initiative focuses on the chronically homeless unsheltered population and works to provide options that allow them to remain stably housed. In Denver, the HCC component of the All In Mile High initiative identified a need for more non-congregate shelter beds to effectively re-house people living in large encampments. Figure 2 below depicts the typical process from Coordinated Entry to a permanent housing solution. Denver condenses the steps between temporary shelter and a permanent housing option through their HCC. Cleveland similarly condenses this process but starts with street outreach. In both cities, the HCCs help speed up the outlined pathway to housing, that may have alternatively been determined through Coordinated Entry, by guiding individuals through the process while prioritizing getting housing or shelter as quickly as possible. HCCs expedite the re-housing process, visibly and tangibly reducing the number of people sleeping outside and supporting these individuals in getting stabilized.

Source: HUD Training on “Notice Establishing Additional Requirements for Coordinated Entry” (March 2017).

Case Study

Denver, CO

Housing Command Centers: An Emergency Response to Homelessness

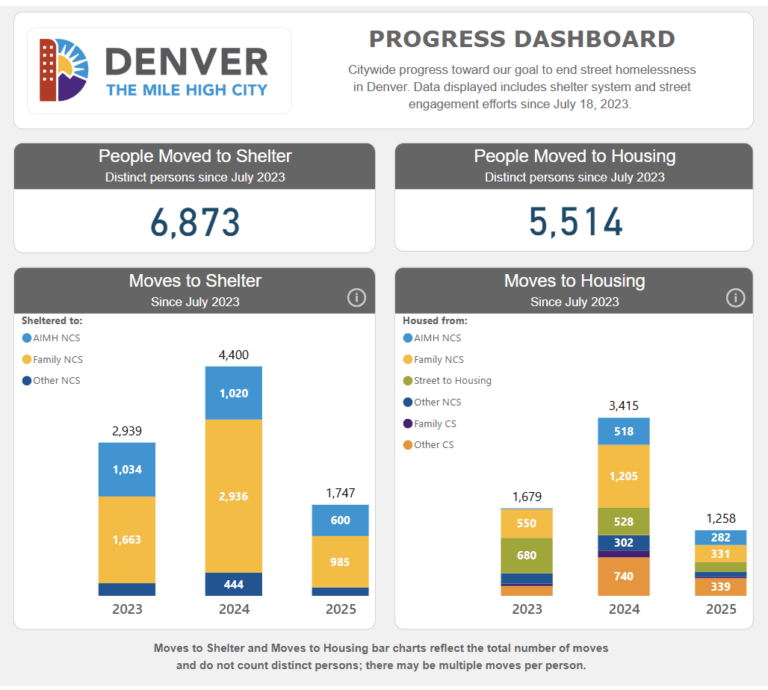

Denver has made remarkable progress toward ending street homelessness in recent years. Current Mayor Mike Johnston, who assumed office in July 2023, campaigned on this issue and on his second day in office declared a State of Emergency on Homelessness, setting a goal to house 1,000 people by the end of 2023, and end street homelessness by the end of his first term in 2027.

Read More About Denver, CO

Case Study

Cleveland, OH

Housing Command Centers: An Emergency Response to Homelessness

Cleveland has also made significant progress in ending unsheltered homelessness using a Housing Command Center approach. After observing a concerning increase in people sleeping outside during the winter of 2023-2024, Mayor Justin Bibb recognized that addressing the issue required a greater sense of urgency and new approach.

Read More About Cleveland, OHHousing Command Centers

Housing Command Centers can be successful in any community that has solid funding, ideally including a flex fund, a centralized unit acquisition team, a robust base of homeless assistance providers with strong case management capacity, and an identified decision-maker with influence over existing systems and an appetite for thinking differently. With these pieces in place, it is also crucial to maintain a reliable database of people and their needs to be able to understand progress toward re-housing in real time. Organizations such as Community Solutions have created a blueprint for using data to drive action toward ending homelessness through Housing Command Centers. Their Built for Zero initiative includes nearly 150 participant cities committed to the goal of reaching functional zero. A key component of Community Solutions’ methodology is “assembling an accountable, community-wide team,” or a Command Center, to ensure that each agency or organization feels the necessary level of accountability and is able to leverage quality data for impact. With several jurisdictions implementing this approach, it has become evident that a successful Housing Command Centers include three core components:

Focus and Prioritization From Senior Leadership: As national homelessness rates continue to rise, systemic improvements are needed to remove bottlenecks and accelerate the re-housing process. This type of system redesign requires significant focus from leadership combined with resources, as was the case in Denver and Cleveland. Mayors Johnston and Bibb announced comprehensive initiatives focused on homelessness, holding themselves accountable to numeric goals. Cities taking a more active role signals their acceptance of responsibility for the issue and provides greater credibility to the response. Disaster response efforts prioritize rapid, coordinated action to secure housing for those affected, and the homelessness crisis demands a similarly structured, housing-first approach. If communities can swiftly re-house individuals after disasters, they should apply the same urgency and methodology to homelessness, without waiting on solutions for the larger affordable housing crisis.

Collaboration to Wield Collective Power: Homelessness is a multi-faceted issue and requires collaboration across numerous entities including, but not limited to, government agencies, service providers, and private landlords. As is typical in emergency management and disaster response, however, some hierarchy is needed to expedite decision-making, meaning that there needs to be a person in charge of building trust and relationships and ensuring coordination across service providers, landlords, and the public sector. Clutch Consulting, a group born out of Houston’s success, helps communities designate roles for different teams and establishes workflows for successfully and expediently re-housing individuals. By-name data is also crucial for effective coordination and response so that disparate entities can keep track of each individual and their specific needs.

Flexibility to Iterate and Adjust: Each community faces unique challenges, and an effective Housing Command Center must adapt and refine its approach through small-scale trial and error. Cleveland, for example, spent a month piloting its program before launching its HCC and started with people experiencing chronic unsheltered homelessness, while Denver set an initial six-month re-housing goal, which they then built upon with a second year-long target. Houston’s response started with veterans’ homelessness and broadened from there. Best practices suggest beginning with larger encampments to concentrate resources and address the broadest range of needs, ensuring the system has been tested to scale effectively. It is also best practice to have a local team negotiate with landlords to assess a fair price for the units and to have a flex fund when possible to address smaller miscellaneous needs that enable successful permanent rehousing.

The Path Forward

With these three core components, and an influx of one-time funding for system redesign followed by sustained funding, a Housing Command Center can serve as a powerful tool to effectively reduce homelessness. Though a robust HCC approach requires significant investment, it is important to consider that cities are already paying the cost of homelessness, not only by having people living outside, but through hospitalization, medical and emergency room treatment, incarceration, emergency shelter, and mental health service costs. As a recent study in Dallas and Collin counties found, these costs amount to roughly $43,000/year per person compared to the estimated $26,000/year per person it takes to permanently house someone through the Housing Forward HCC. Keeping the cost of inaction in mind along with successful rehousing numbers can help make the case for sustained funding for Housing Command Centers. Treating homelessness as an emergency brings necessary focus and urgency to accelerate the outflow of people from homelessness into stable housing, eventually outpacing the inflow of people into homelessness.