Mixed-Income Public Development Model: Local Housing Finance Agency Innovation

AUTHORS: Paul Williams, Ashwin Warrior, Chelsea Andrews, Ken Silverman, Lourdes Castro Ramirez, and Michael Saadine

Key Points

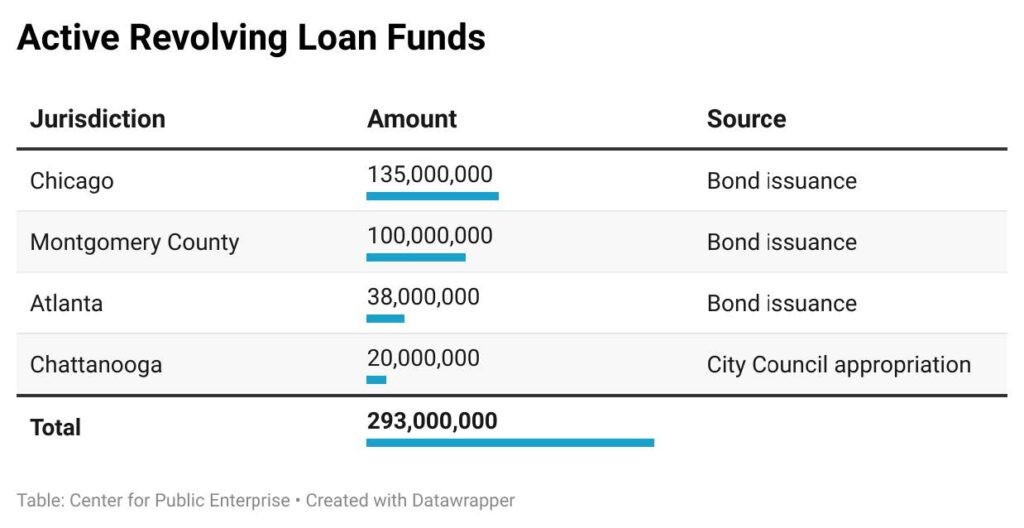

- Montgomery County, Maryland created a $100 million Housing Production Fund, which is a new way to generate self-sustaining investments in mixed-income housing developments.

- Cities across the country have replicated this approach, creating a new type of public partner in the development process.

- These revolving loan funds invest in housing developments, drive affordability, and ensure public ownership of housing developments.

As the national housing crisis grows in scope and severity, traditional affordable housing solutions are proving insufficient. The affordable housing market has grown reliant on the Low- Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) and federal vouchers, along with the ecosystems that have developed around them. However, these resources do not stretch as far in the context of rising construction costs and rents and increasing uncertainty regarding federal support and the macroeconomy.

To meet the crisis head-on, states and localities are deploying a new toolset. Housing Finance Authorities (HFA), state or local government, or quasi- overnmental agencies focused on providing financing for affordable housing possess capabilities beyond the traditional toolkit of LIHTC and associated tax-exempt bonds. Certain creative state and local agencies have begun leveraging additional mechanisms to drive a Mixed-Income Public Development Model, filling gaps left by traditional programs and resources. State and local governments can deploy revolving loan funds, low-cost permanent financing, and in some cases property tax relief to enable public-led development of affordable and mixed-income housing.

The Challenge This Tool Solves

The affordable housing development ecosystem is largely built on powerful, but currently insufficient federally authorized and funded tools including LIHTC, associated tax-exempt Private Activity Bonds (PABs), and vouchers. LIHTC is often oversubscribed by nearly three times, while only one in four eligible households receives federal assistance (including vouchers).

Beyond shortfalls in existing programs targeting lowest-income residents, challenges hinder

efficient affordable and mixed-income housing development. Market-rate private equity investors face high capital costs and typically avoid the complication of mixed-income projects, often lacking the capacity to properly manage the requirements accompanying affordable units, such as income verification. The development market also faces challenges across income levels in the current high-construction cost and high-interest rate environment. These factors combine to create a funding gap for mixed-income, public-led developments. Mixed-Income Public Development can create the conditions to fill this gap.

Types of Communities That Could Use This Tool

Affordability in the mixed-income development model comes from savings in financing costs and reduced operating costs through property tax relief. The model also relies on sufficient difference between market and affordable rents to permit a level of cross-subsidization. As such, this approach works best in areas with strong rental markets, and less effectively in rural or underinvested areas where private investment is not occurring. Generally, where private

development successfully pencils, this model should operate successfully by bringing in public financing tools and in some cases property tax relief to reduce costs. In hot markets where rents are rising rapidly, this model can be a potent tool to secure affordability in high-opportunity areas.

This paper focuses largely on the success of the Montgomery County Housing Opportunities Commission (Montgomery County is a region in Maryland and suburban Washington DC). The entity (HOC) was established in 1974 and acts as the County’s designated Public Housing Authority and Housing Finance Agency. More recently, the commission collaborated with Montgomery County Government to create the $100 million Housing Production Fund (HPF). We also highlight efforts in Chicago, Atlanta, and Chattanooga, demonstrating the breadth of community types that can benefit from the model.

Large jurisdictions with robust housing demand and well-staffed public agencies may want to begin by establishing revolving loans to achieve maximum benefit and scale from this model. However, many jurisdictions have existing housing trust funds or other low-cost loan or grant mechanisms often used to provide gap funding for LIHTC projects. Public Housing Authorities (PHAs), HFAs, or municipal housing departments could identify specific high-value development projects, develop partnerships with private developers, and use those existing authorities to issue low-cost construction loans. These projects could be based on government-owned land primed for redevelopment, with developers chosen through RFP, or could be done in partnership with private developers on stalled projects. A public entity could partner with the private developer, create a new publicly owned holding company to receive the loan, and proceed. This approach resembles “80/20” developments commonly undertaken with FHA Risk Share by private developers in New York City, but with the added benefits of public ownership. This allows municipalities to begin producing housing while figuring out the legal, financial, and political issues surrounding capitalizing a larger revolving loan fund or potentially creating a new public entity.

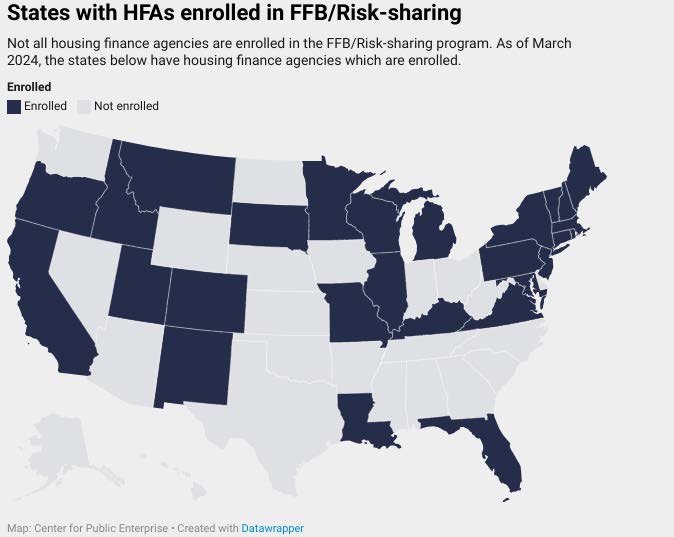

The involvement of the HFA that is part of the HUD-HFA Risk Share program can enhance the tool’s impact for communities with a participating HFA. The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) partners with the HFA to enhance HFA credit, lowering the cost of capital. The Federal Financing Bank (FFB) can also step in and purchase Risk Share loans, further reducing the cost of capital. These Risk Share loans can be taxable or tax-exempt and represent an opportunity to recycle Volume Cap that cannot be used to generate new 4% tax credits but can provide tax-exemption for a Risk Share loan.

Expected Impacts of This Tool

HOC’s $100 million fund is expected to have approximately 10-to-1 leverage over 10 years (more details in Case Studies section below), catalyzing $1 billion of mixed-income development capital. If the top 50 metros were generated production funds of similar per-capita scale, these funds of approximately $20 billion could catalyze $200 billion of mixed-income development over 10 years.

The Mixed-Income Public Development Model provides new tools to address the housing crisis without drawing upon existing scarce resources. A well- executed mixed-income public development model can expand available housing resources beyond LIHTC, tax-exempt bonds, and vouchers to enable more production as those resources are often exhausted or inadequate to the increasingly complex tasks of the capital stack.

Almost all new affordable housing construction and rehabilitation across the country is currently built using the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC). By most standards, this tax credit program has been extremely successful, responsible for the construction or preservation of roughly 3.85 million affordable homes since its inception in 1986, but it remains oversubscribed.

Concurrently, states are increasingly reaching the limits of their tax-exempt Private Activity Bonds (PABs), with 31 states either oversubscribed or near their annual PAB cap. Each year, the federal government sets limits on the amount of PABs each state can issue on a per-capita basis, based on population. The advantage of a PAB is that the interest paid to any bondholder is exempt from federal income tax, meaning bondholders are willing to accept lower interest rates, in turn enabling reduced borrowing costs for loans made with bond proceeds. PABs regularly finance public facilities like schools and sewers, as well as student loans, but are also used for housing. Any project using 4 percent credits under the LIHTC program must have 50 percent of its costs financed through PABs, so having space under a state’s PAB cap is important for a well-functioning LIHTC program. To the extent that mixed-income public development can be

accomplished without tapping these scarce resources, state and local governments can better target those resources to the projects serving the deepest need.

Housing affordability is also routinely achieved through various voucher or rental subsidy programs. The largest program is the federal Housing Choice Voucher program, but many cities, such as Chicago and Washington D.C., also fund local rental subsidy programs. These programs typically ensure a household pays no more than 30 percent of their income toward rent, with the subsidy covering the difference between that amount and a payment standard tied to market rents. These programs are crucial to serving some of the lowest-income households in the country. While the mixed-income public development model does not deliver the same levels of affordability a voucher program provides, it also does not rely on the availability of vouchers for project feasibility. A key advantage of this model is that it can seamlessly layer on top of existing affordable housing production a particular community undertakes, ensuring affordable housing production continues stop when LIHTCs, tax-exempt bonds, or vouchers run out.

A mixed-income public development model should supplement existing affordable housing production, not compete for limited funds. In fact, this model can work well with a state’s existing LIHTC pipeline by providing an alternative path for qualified projects that did not receive LIHTC awards and could be reworked as mixed-income deals.

Mixed-Income Public Development Model

The affordability achieved under the Mixed-Income Public Development Model is enabled by three key elements:

- A revolving loan fund to provide a portion of construction financing;

- Low-cost permanent financing enabled by existing HUD and Treasury programs; and

- Mission-aligned mezzanine financing to bridge gaps between construction and

permanent financing.

Additional considerations beyond the financing sources themselves include:

- Governance in a majority public ownership structure; and

- Asset management responsibilities for the public sector.

In this section, we describe each of these elements in detail and show how they fit together to deliver publicly owned, mixed-income housing.

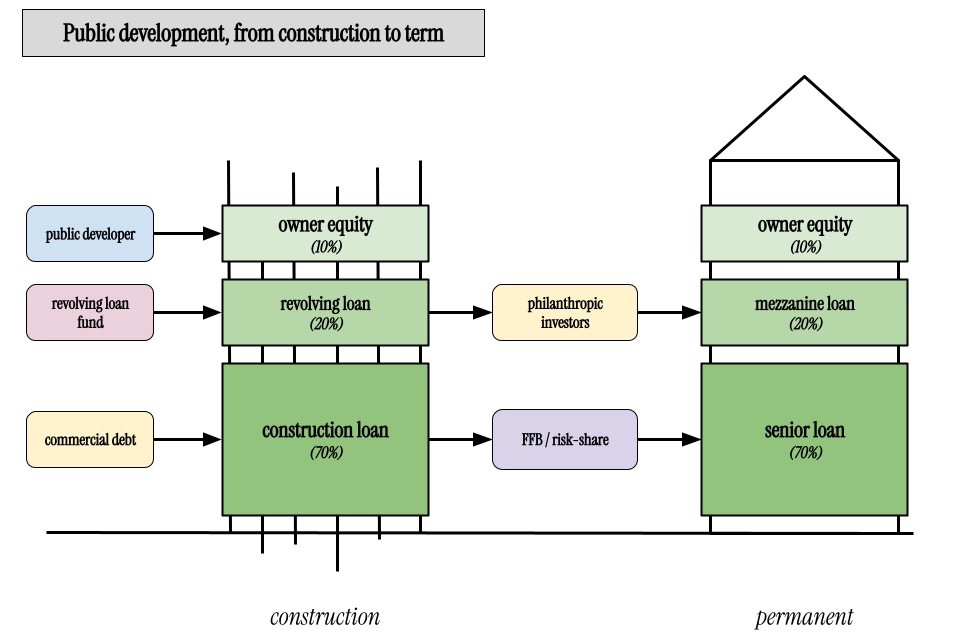

A Revolving Loan for Construction Financing

Financing multifamily housing development typically occurs in two phases. The first, construction financing, involves equity and debt developers assembling to complete pre-development and construction activities. In a market-rate transaction, most costs are paid for by a short-term (12- to 18- month) construction loan from a bank covering the majority of pre-development and construction costs. The remaining costs would be covered by either the owner’s equity or a private equity investment. Second, once projects are built and leased, projects convert to permanent financing, paying off and replacing construction loans with longer-term notes. Because there is less risk involved with a completed, occupied building, permanent financing carries lower interest and is typically paid for out of the net operating income of the building (i.e., rental income less expenses).

In the current high-interest-rate environment, construction loan sizes are decreasing. In lowerinterest- rate environments, construction mortgages might cover two-thirds of a project’s cost. In today’s conditions, that loan-to-value ratio can be much lower, closer to just 50 percent, requiring developers to rely on private equity investments to cover gaps, which often come with expectations of double-digit returns, driving up overall construction costs.

The public mixed-income development model overcomes this hurdle by replacing private equity investment with funds from publicly funded revolving loan funds. Revolving loan funds provide roughly 20 percent of the construction costs and then are replaced when the project converts to permanent financing, allowing the fund to make further investments.

Low-Cost Permanent Financing

At stabilization (after the construction and lease-up of a property), senior debt is converted to a permanent mortgage. Here projects can leverage low-cost public financing through programs such as Section 542(c) Risk Share Program. Risk Share is a federal program allowing the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) to partner with qualified state Housing Finance Agencies (HFAs) to share the risk on mortgages issued by the HFA. The Risk Share program provides credit enhancement to HFA bond and debt issuances through FHA mortgage insurance, resulting in lower borrowing costs. HFAs are then able to pass on these savings to multifamily borrowers, resulting in lower financing costs that promote the development of affordable housing. Loans made under the program can finance up to 80 percent of the project’s total cost with competitive interest rates due to reduced risk.

There is an add-on to the Section 542(c) Risk Share Program wherein Treasury’s Federal Financing Bank (FFB) purchases Risk Share loans. This provides a major advantage to participating agencies; instead of having to source capital for loans from the market or their existing balance sheet, they can have those loans funded directly by FFB. The key advantage of Risk Share paired with FFB financing regards enabling sources of permanent financing that do not rely on tax-exempt bonds, which may be scarce depending on the state. Projects using FFB/Risk Share for permanent financing do not trigger prevailing wage requirements because the federal government is not assisting with the construction phase, but all Risk Share projects are required to provide either 20 percent of units at 50 percent AMI or 40 percent of units at 60 percent AMI and adhere to federal environmental requirements. Generally, the interest rate on FFB/Risk Share loans equals the 10-year Treasury rate plus 100 basis points. Over the last eight years, interest rates on FFB loans made for new construction and substantial rehabilitation have ranged from 1.89 percent to 6.32 percent.

Although the Risk Share program is described as a program for housing finance agencies, regulation defines a housing finance agency as any public body empowered to finance housing activities. This leaves open the possibility that other state-chartered entities, such as public housing authorities, could access Risk Share and FFB directly. The Center for Public Enterprise is currently working with several jurisdictions to explore different methods of accessing the program.

Recent changes to the Risk Share program have made it even more useful for new development. The Treasury recently announced it is instituting an interest rate “collar,” to the program to mitigate the risk posed by interest rate variation between the construction and permanent financing periods. Between the start of construction and the acquisition of a permanent mortgage, interest rates can fluctuate — sometimes significantly. If a developer builds a project when rates are 5 percent, but completes it when rates are 8 percent, they might find themselves in a bind. With the new change, when a project is approved for FFB/Risk Share, it will lock in a so-called rate collar, providing certainty that the eventual rate on the permanent mortgage will be within a specified range, or collar.

While Risk Share and FFB bring significant benefits, it is possible to execute the mixed-income public development model with other permanent financing sources. For example, if a state has excess bond volume cap, permanent financing could be arranged via a tax-exempt bond issuance. Financing can also be provided through conventional private bank products, if the administrative and compliance requirements of using FHA Risk Share do not outweigh the value of lower interest expenses, particularly if the business cycle is in a stage in which interest costs are less of a cost driver.

There is a long history of using public financing for mixed-income projects. HFAs have successfully financed 80/20 deals (80% market and 20% affordable) as far back as the 1970s using tax-exempt bond financing. The challenge has always been that these projects pull from a finite source of tax-exempt bond volume, and states often, and rightly, prioritize 100 percent affordable deals with LIHTC over mixed-income projects. Using FFB/Risk Share allows projects to proceed even when tax-exempt bonds are oversubscribed.

Tax-exempt bond issuances can also be considered as a source of lower-cost permanent financing with fewer programmatic limitations. However, municipal bonds can come with challenges such as limited non-issuer ownership, and variability in costs due to the effects of the financial capacity and rating of the issuing municipality. Using tax-exempt bonds would also use bond volume cap, which may be better allocated to other financing activities such as single-family first-time buyer programs and various other multifamily projects.

Mission-Aligned Mezzanine Financing

At the conversion to permanent financing, projects are typically able to secure senior loans with more favorable loan-to-value ratios than the loan-to-cost they received on construction financing. In some cases, this allows permanent loans to pay off the revolving loans.

In projects where permanent loans are not large enough to completely pay off construction loans, the model typically relies on a source of mission-aligned capital — most often from community development financial institutions (CDFIs) or philanthropy—to pay down construction loans. The Montgomery County Housing Opportunities Commission typically underwrites its projects conservatively under a worst-case scenario in which projects receive a roughly 10-year mezzanine loan at 10 percent interest. In practice, when HOC goes to market for financing, it can typically secure lower interest rates because it has an attractive product to offer: moderate returns on investment backed by real estate with paying tenants in high-opportunity areas. HOC has historically been able to secure terms below their “worst-case” benchmarks.

Communities seeking to replicate this model could turn to local philanthropy as a potential lender for the mezzanine debt at conversion to permanent financing. There is natural alignment between public mixed-income housing projects and philanthropy seeking sensible investments that have immediate impact on their local communities. More broadly, a national source of consistent mezzanine financing to replace a revolving loan fund investment could help this model expand into areas that would otherwise struggle to attract such capital. If replacement mezzanine financing for stabilized assets is not available at a reasonable cost, jurisdictions could leave the low-cost construction loan in place for a longer period or replace it with another source of local financing. This would reduce the leverage on the production fund by slowing its revolution but would still generate valuable new affordable housing outside of what federal subsidy can support.

Certain entities have the capability to combine these financing mechanisms with property tax relief, further contributing to affordability and allowing the development costs to “pencil”. The National Housing Crisis Task Force has published an additional tool on this subject, Right-Sizing Property Tax Incentives to Increase Housing Affordability.

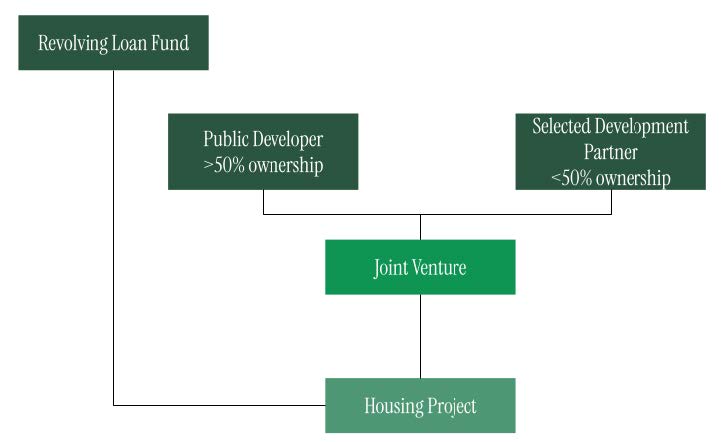

Governance Structure: Public Ownership

Majority public ownership, in contrast to other public-private arrangements, leaves control of the affordability of housing units in the public sector’s hands and ensures that the public sector sets the policy regarding how units are developed and managed. It also allows public retention of value coming from these projects as they appreciate over time and reinvesting that value in additional affordable housing developments throughout the community.

In Montgomery County’s case, the public ownership entity is HOC, which serves as both a PHA and local housing finance agency (HFA). HOC seeks to maximize affordability on all its projects. All market-rate units are voluntarily rent stabilized (rent increases are based on rental Consumer Price Index), and income-restricted units in the property are maximized against cash flow requirements. In structuring projects, HOC will add affordable units, or deepen their affordability, to the greatest extent possible while still maintaining a financially self-sufficient building.

Perhaps more importantly, the county can add additional affordable units at no cost in the future. When mixed-income properties are refinanced, for example, in 10 years, any reduction in annual debt service costs can pay for the addition of more income-restricted affordable units in properties. Without majority public ownership, this is significantly more difficult especially when it reduces the profitability of properties — a challenge for a private, for-profit entities with fiduciary responsibilities to maximize profit.

Under the mixed-income public development model, the public entities bring tremendous value to projects — and retain that value. In HOC’s case, the county often brings low- or no-cost land, significantly reduced cost capital, and reduced or eliminated property taxes to projects. In exchange, HOC takes majority interest in the properties. And, despite early concerns that developers would balk at the proposition of not owning their properties outright, HOC has so far been inundated with requests from developers to partner on projects.

To initiate projects, public entities enter into joint venture agreements with private development partners, with the public entities taking majority stakes. Each property is set up as its own individual Limited Liability Company (LLC). This insulates the parent company or sponsor from lawsuits or liabilities stemming from individual projects. Housing authorities or public entities would negotiate development agreements covering items including, but not limited to: ownership structure, land and site control, development responsibilities and fees, asset mana gement and resident service agreements, cash flow distribution splits, and decision-making processes.

Public authorities and private developers would also negotiate options for the private partners’ exit from the deal. This could take various forms, including developers being bought out after a specific amount of time or having an option to convert their upfront equity to debt.

Asset Management

Once a property is built and stabilized, agencies have the flexibility, as they do now, to provide their own property management or contract with an outside entity for property management services.

Moving toward this type of model could represent a change in the business operations for some PHAs, which for a long period of time were permitted to centralize accounting and property management, as opposed to adhering to project-based methods more common in the private sector.

It will also require stewardship of these assets as true mixed-income communities. While appearing simple on the surface, getting the asset and property management right for these projects requires thoughtful and attentive implementation that goes beyond simply the financial performance of buildings.

Case Study

Mixed-Income Development Model: Montgomery County, Chicago, Atlanta, and Chattanooga

Mixed-Income Public Development Model: Local Housing Finance Agency Innovation

As of the time of publication, at least four communities are actively implementing the mixed-income public development model, with numerous other localities and states exploring similar implementations.

Read More About Mixed-Income Development Model: Montgomery County, Chicago, Atlanta, and ChattanoogaDiffusion and Scaling Mixed Public Income Development

The role of intermediaries is key in setting up and administering these complex structures. The nonprofit Center for Public Enterprise (CPE), focused on public sector economic development tools, has taken a leading role. The Local Initiatives Support Coalition (LISC) also works directly with localities on financial and operating structures. Here we highlight CPE’s role and strategy for impact.

Center for Public Enterprise works with states, cities and counties to implement mixed-income public development models. CPE has been the leading nonprofit think tank providing technical assistance to public sector organizations exploring the mixed-income public development model, which consists of the following six stages:

1. Market Testing: Before launching a new program, it is important to test the market for the targeted location through a high-level financial model. This involves inputting various data points related to the local market, such as rental rates, construction costs, potential subsidies, and demand for mixed-income housing. CPE and similar entities can identify and define the initial assumptions that underpin the model. These assumptions are crucial, as they directly impact the model’s output and the feasibility assessment.

The model tests different scenarios and helps determine the potential return on investment, the level of subsidies needed, and the types of projects that align with the mixed-income public development model.

2. Pipeline Development: The next stage of program launch is identifying potential development opportunities. This includes looking at stalled local developments to identify projects that have stalled due to financing, regulatory, or other issues and assessing if they can be revived as mixed-income projects, analyzing Publicly Owned Parcels, reviewing the Existing Pipeline of projects that are already in the local jurisdiction’s pipeline or that have previously applied for funding to see if they fit the mixed-income program, and Socializing the Program by with developers, community organizations, and other stakeholders to explain the program and encourage participation.

The objective is to create a robust pipeline of potential mixed-income development projects. This ensures that the program has a steady flow of opportunities and increases the likelihood of successful implementation.

3. Institutional Framework and Governance Design: While there are similarities across existing programs that have established these tools, each jurisdiction should consider optimal ways to structure and manage the mixed-income program. This involves creating a Program Framework to decide where the program is best housed and how the benefits of the model can be maximized, designing the Project/Deal Flow process for how projects will be identified,

reviewed, approved, and financed, and facilitating Stakeholder Meetings with staff, city officials, developers, and community groups to gather input and build consensus. Creating a clear and effective governance structure for the program ensures accountability, transparency, and efficient decision-making.

4. Financial Structure Design: Jurisdictions should explore various financing for mixed-income projects and develop a plan for a Revolving Construction Loan Fund that provides short-term loans for construction, including identifying different funding sources (senior debt, mezzanine debt, equity), how they can be combined to fit the Capital Stack Arrangements to finance projects, exploring Senior Debt Options like Section 542 Risk-share/FFB, recycled volume cap, and essential function bonds, working on Statewide Organization Coordination with statewide organizations to explore a potential “passthrough” senior debt pathway, and investigating Mezzanine/Subordinated Debt Options like partnerships with CDFIs (Community Development Financial Institutions), philanthropic organizations, and regional banks. Taken together, this would be a comprehensive and flexible financial strategy that can attract investment and maximize financial viability.

5. Project-Level Financial Modeling: Next, local jurisdiction create detailed financial models for specific projects, including: Project-Level Pro Formas for a particular project, including construction costs, operating expenses, rental income, and financing costs, creating Term Sheets that outline the key terms of a financing agreement, such as loan amount, interest rate, and repayment schedule, and working on Sample/Pilot Projects by creating pro-formas and term sheets for a few initial projects to test the program’s feasibility and refine the process.

6. Capacity Development: As jurisdictions launch new programs, it is important for managing entities to build internal capacity to manage mixed-income programs. This includes identifying Staffing Needs for local jurisdictions, such as underwriters, project managers, and financial analysts, and sources of Training and Technical Assistance that can provide guidance and support to staff on financial modeling, project management, and other relevant skills. This ensures that jurisdictions have the necessary skills and resources to successfully implement and manage programs over the long term.