Land Use, Permitting, & Building Code Reform: A Path Forward

AUTHORS: Benjamin Preis, Ph.D. and Emily Desmond

Developed with contributions from Research Advisory Committee members Emily Hamilton and Alex Horowitz

Key Points

- States and local governments both have a role to play in simplifying zoning and land use rules to allow for more housing in communities where people want to live.

- Building code and permitting reform similarly advance the goals of providing more housing, more efficiently and quickly.

- These reforms have broad public support and bipartisan success, with places as diverse as Montana, California, Utah, Massachusetts, and more implementing similar sets of changes

Land use, permitting, and building code reform have made tremendous strides in the last decade. Many successes have emerged from a groundswell of local activism, combined with a sustained chorus of experts and advocacy organizations proposing specific solutions. However, many of the solutions thus far have been ad hoc and reactive — solving individual bottlenecks, obstacles, or barriers — rather than holistic or structural in nature.

This tool outlines the policy action for land use, permitting, and building code reform, while providing an overview of federal, state, and local efforts.

The Challenge This Tool Solves

Land use regimes, permitting processes, and building codes have grown increasingly restrictive, preventing housing supply from effectively responding to increases in housing demand. That means that, today, it is harder to build a wide variety of home types in a wide variety of places. This results in fewer homes, fewer choices, less affordability, and less availability of housing across communities nationwide.

Types of Communities That Could Use This Tool

Nearly every community in the U.S. limits the type of housing that can be built in their community through planning and zoning laws and processes. These local regulations constrain housing options through use restrictions, density limitations, setback requirements, minimum lot sizes, and even explicit prohibitions on housing types such as duplexes, triplexes, townhomes, and small apartment buildings, forms that often exist in neighborhoods developed before zoning became widespread. Further, many local governments operate their own permitting offices. Building codes are often codified in state law and/or regulation and implemented through a partnership between state and local governments. Since land use, permitting, and building codes are purely the province of state and local government, reform-minded policymakers at these levels of government have significant opportunity to increase housing production by adjusting regulatory frameworks.

Expected Impacts of This Tool

Land use, permitting, and building code reform can substantially reduce new development costs. On upzoned parcels that previously only supported the development of expansive single-family homes, homebuilders could instead develop small apartment buildings affordable to teachers, firefighters, and service workers. By expanding home choices in a given community, reducing the time it takes to get a building permit, and requiring common-sense building safety codes, cities can reduce regulatory barriers and allow for more housing.

Modern building codes and land use regulations in the U.S. emerged during the Progressive Era of the late 19th and early 20th century. These regulations’ complex histories involve competing narratives of health and safety on the one hand, and exclusion and regulatory capture on the other.

In recent years, it has become widely acknowledged that land use regulations increase the cost of homes and decrease the supply of homes, with deleterious effects on the environment, cities, and residents. Building codes, too, can be associated with increased housing costs, yet there is a necessary cost-benefit analysis between safer, more energy efficient buildings and increasing the cost of new construction that makes housing out of reach for households.

In the U.S., local governments typically control land use regulation through zoning, operating under the direction of state statute. This has been the case since the early 20th century, when the Standard State Zoning Enabling Act was distributed by the Department of Commerce in 1924. This model legislation was adopted by all 50 states, and, as of 1988, was still in force (albeit in modified form), in 47. The Supreme Court of the United States cemented the legality of zoning in its decision Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co., (272 U.S. 365 1926). A century later, this has resulted in the U.S. having 50 legal regimes governing the adoption, modification, and enforcement of approximately 30,000 distinct zoning codes.

Building codes have evolved along a parallel path. In the 21st century, houses with only one or two units are generally governed by the International Residential Code (IRC), while multifamily buildings are governed by the International Building Code (IBC), both of which are model codes promulgated on a triannual cycle by the International Code Council (ICC), a non-governmental organization, that are then adopted, with or without modifications, by states or localities.

Building codes are distinct from zoning codes as building code adoption and implementation need not be carried out by the same entity — state building codes may be enforced by cities or counties, the so-called “Authorities Having Jurisdiction.” According to the U.S. Census Bureau, more than 20,000 such authorities exist nationwide. The promulgation of building codes also varies significantly state-to-state. Eight states have statewide building codes, 16 states have predominantly local building codes, and 26 employ a combination of state and local building codes, wherein there is a statewide building code, with some localities permitted to amend or replace the state building code.

Both zoning and building codes present complexity and barriers to necessary housing production in their current forms. The process to acquire building permits — which requires developers to comply with zoning, building, environmental review, stormwater management, traffic mitigation, and a host of other rules — also slows down and increases the cost of production. Modifying only building or zoning codes presents a missed opportunity. Additionally, both present complementary challenges related to local government process and permitting.

In the past decade, an increasing awareness of the history, cost, and exclusionary nature of zoning spawned an extensive campaign to reform zoning at both the state and local levels. While predominantly Democratic states like California and Oregon were among the first to implement statewide zoning reform, state- level efforts to reform zoning are notably bipartisan in nature, with Republican strongholds including Utah, Montana, and Florida passing both comprehensive and targeted zoning reforms. Like land use and building code reform, permitting reform has also taken place at both the state and local level. As state law grants local “authorities having jurisdiction” the power to oversee the permitting process, some states have compelled these jurisdictions to streamline and issue permits more quickly.

Local governments have also independently passed zoning reforms. Minneapolis notably eliminated parking minimums and single-family exclusive zoning through its comprehensive planning process that took effect in 2020. Cities like Alexandria, VA, and Austin, TX, have enacted similar reforms. However, eliminating single-family exclusive zoning — without changing requirements related to setbacks, floor area ratios, parking, or other rules — can lead to paper only changes, where, though more homes are technically allowed on a given lot, there are no tangible impacts on the number of homes that can be built.

Reforming Land Use, Permitting, & Building Codes Processes

Land Use Reform — A Summary

Land use reform is a broad category, encompassing more than simply increasing unit density on a given lot. Indeed, cities, counties and states have enacted or contemplated numerous changes to land use regulation. Learning from the early movers, comprehensive zoning reform that allows for more homes of all shapes and sizes, and lifts local restrictions preventing affordable home choices, should include some version of all the following:

Reform |

Leading Examples |

|

Allowing up to six homes or apartments by-right on every parcel that currently allows for a single-family home |

Washington State (near transit stops) Portland, Oregon (citywide) |

|

Allowing for up to two Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) of 1,000 square feet by-right |

California, Arizona, Colorado, Hawaii, Maine, Montana, Rhode Island, Washington, among others Numerous cities have also passed ADU reform. |

|

Decreasing minimum lot size requirements to 1,400 square feet, to legalize townhouses |

Houston’s reforms to reduce the minimum lot size from 5,000 square feet to 1,400 square feet |

|

Reducing or eliminating parking minimums to decrease the cost of new construction |

Minneapolis Montana SB 245 California SB 1069 (2016) |

|

Allowing apartment buildings by-right on commercial or industrial land |

|

|

Making it easier for homeowners and developers to utilize lot splits to increase density, in combination with changing minimum lot sizes |

California SB 9 (2021) |

|

Eliminating explicit unit counts or maximum dwelling units from the zoning code, allowing for building code requirements to set density on a given lot |

|

|

Legalizing co-living with shared facilities and smaller units |

Seattle, WA and Minneapolis, MN have both legalized co-living in their zoning codes Austin, TX removed limits on the number of unrelated individuals living together |

Land use reform can also be targeted in particular ways, including:

Reform |

Leading Examples |

|

Requiring increases in density around transit stops, in pursuit of Transit-Oriented Development |

|

|

Granting affordable housing greater density allowances than market-rate housing |

Cambridge, MA’s Affordable Housing Overlay |

|

Changing the rules governing zoning changes |

|

|

Allowing manufactured housing by-right in zones that otherwise allow for single-family homes |

Maryland HB 538 (2024) Maine LD 337 (2024) |

Many states have also passed more comprehensive housing supply bills potentially impacting land use. For instance, Montana, Colorado, and California all have laws requiring localities to estimate and plan for growth, changing their land use regulations in line with those growth projections.

Many best practices have been identified and codified by existing national organizations. The Mercatus Center at George Mason University tracks land use reform efforts at the state level every year, Pew Charitable Trusts has similarly produced research showing the variety of reform efforts, while the American Enterprise Institute has produced an entire set of policy briefs devoted to “light-touch density,” or what many others call “missing middle” housing of duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes, ADUs, townhouses and small apartment buildings.

Similarly, the National League of Cities, through their Housing Supply Accelerator Playbook, includes 14 land use reform strategies that local governments can implement. The National Association of Counties Housing Task Force had land use reform as one of five focus areas, with five actionable steps county governments can take. The National Governors Association’s Center for Best Practices has convened a state Housing Policy Advisors Institute to identify best practices at the state level.

It is also important to note that land use reform is not new, though its success certainly is. National studies, including the Douglas Commission on Urban Problems in 1968, the 1982 President’s Commission on Housing, and the Advisory Commission on Regulatory Barriers to Affordable Housing in 1991 all examined, at least in part, the effects of land use and zoning regulations on limiting the production of housing. Indeed, many of the contemporary changes date back to those proposals; for example, President Reagan’s Commission on Housing recommended eliminating minimum lot sizes, allowing manufactured housing in all residentially zoned areas, and removing density requirements except for where there is “a vital and pressing governmental interest.”

Permitting and Building Code Reform — A Summary

While zoning and land use reforms have garnered headlines, housing advocates have identified permitting and building codes as distinct but equally important regulatory barriers requiring coordinated reform.

Though zoning regulations bear a resemblance across jurisdictions, permitting processes are less uniform, leading to difficulties in generalizing permitting changes that can take place nationwide. Permitting reform can include:

- Exempting certain housing types from environmental review;

- Increasing the speed at which jurisdictions must issue permit decisions;

- Providing “concierge” service and/or “fast track” service for affordable housing developments;

- Authorizing third-party reviewers; and

- Limiting impact/development fees that municipalities can charge.

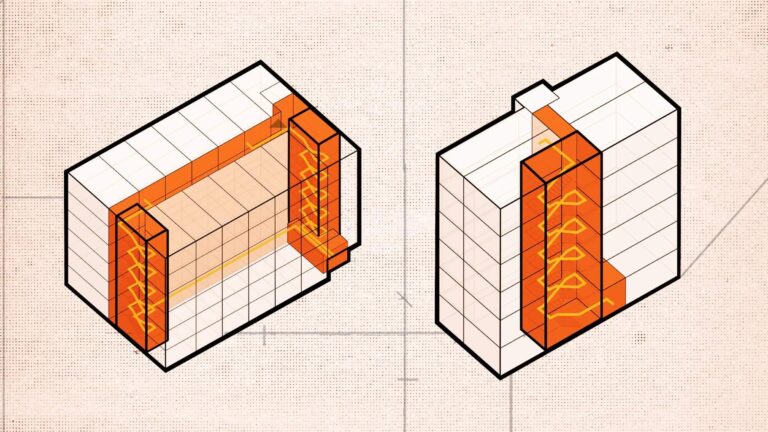

Building code reform in the U.S. has recently focused predominantly on “single stair” reform. Under the International Building Code, buildings over three stories typically require two means of egress. With exceptions in Seattle, New York City, and Honolulu, most U.S. jurisdictions mandate two stairs in all apartment buildings, reducing financial feasibility for small parcels and increasing per-unit rent due to unleasable space. This differs from many international peer countries, which allow single-stair designs with additional fire protection measures in buildings over ten stories.

The Center for Building in North America tracks single-stair reform in the U.S. In 2024, Tennessee passed a law allowing municipalities to adopt a building code that allows for a single stair for up to six stories, and Knoxville passed such an amendment in November 2024, with Jackson following in December 2024. Connecticut passed a law in 2024 instructing executive branch officials to update the state building code to allow single-stair construction. Other jurisdictions, including California, Oregon, and Virginia have passed “study bills” directing statewide agencies to study the safety and feasibility of single-stair buildings.

Both permitting and building code reforms face implementation challenges in part due to the heterogeneity in state-level building and permitting regimes. While land use regulation primarily occurs locally, building codes are often enacted at the state level, with local jurisdictions given the option to enact amendments to the state building code. However, many states having no statewide building code, leading to each municipality adopting their own. Montana’s recently enacted SB 406 prohibits local building codes from being stricter than the state building code.

Building code reform also presents a challenge of expertise and messaging. While advocates and experts have coalesced around the harms of the current zoning landscape, fire marshals and the general public have proven resistant to building code reform. Thus, building code reform requires careful consideration of messaging and the research necessary to assuage fears of compromising life safety or environmental quality in pursuit of lower-cost housing. For instance, recent research from The Pew Charitable Trusts demonstrates that small, single-stair buildings are incredibly safe.

Building code reform is also taking shape as it relates to modular and other offsite construction. Virginia, Colorado, and Utah have all passed ICC standards to allow for state inspections of offsite housing manufacturing facilities that supersede local inspections, allowing for decreased regulatory costs for modular housing manufacturers.

Principles Behind Land Use, Permitting, & Building Code Reform

Land use reform at the state level offers the broadest, most immediate impact. Further, land use and zoning are important to local governments in the U.S., and localities should retain their ability to create land use and zoning plans. While local governments can and should enact land use reform on their own, and indeed, many localities across the U.S. are doing so, the inclusion of state-level leadership provides some advantages.

First, cities and counties derive their ability to regulate land use from states, allowing for a certain uniformity in land use reform. This Task Force believes that states should amend their laws to require or incentivize localities to reform their land use to allow for a greater variety of housing types; states should provide funding, technical assistance, and support to ensure that all localities are able to meet these new requirements. Housing markets are regional, and housing solutions must also be regional. State-level reforms should address the needs of large cities, small towns and predominantly rural areas. Since local governments get their authority to regulate land use from the state, their land use regulations must factor in the welfare of residents across the state, not just in that locality. State-led land use reform ensures a baseline uniformity, recognition of differences across regions, and predictability for homebuilders and residents. States have taken different approaches to land use reform. Some opt for outright preemption regarding certain practices like requiring ADUs or planning for transit-oriented development. Others, like Montana’s SB 382, require large municipalities to enact a set of pro-growth strategies from a list of 14 potential policies. A third group has sought to encourage pro-housing zoning reforms through incentive programs. For example, New York’s Pro-Housing Community Program, California’s Prohousing Designation, and New Hampshire’s Housing Champion Designation all evaluate local governments on the extent to which they have enacted pro-housing reforms and then provide additional incentives or grants to those cities over those that have not done so. States should identify the reforms that they wish to ensure are in place state-wide — such as eliminating parking minimums, allowing for ADUs statewide, and eliminating bans on manufactured housing — and allow localities to implement those reforms with the support and technical assistance that they need. Recent experience also suggests that, once states have moved the needle on zoning reform, many municipalities will go farther than the state-level requirements.

Second, land use, permitting, and building code reform invites strange coalitions. Land use regulations ultimately limit the private property rights of landholders, while building codes and permitting are government regulations that increase the cost of construction. On the other hand, the origin of zoning in the U.S. can be traced back to segregationist policies that sought to prevent integration in neighborhoods, through either explicitly racial zoning, or economic zoning with large lot sizes and bans on apartment buildings. Land use regulations minimize change, block development, and allow for the privatization of public space. Conversely, land use regulations encourage sprawl, reduce housing options, and increase carbon emissions. With a larger geographic footprint and a more diffuse constituency, state legislators may be able to pass land use reform that would otherwise be impossible at the local level by working with these broad coalitions.

States across the political spectrum, including Oregon, Montana, California, Connecticut, Utah, Washington, Arizona, Vermont, Colorado, Hawaii, Massachusetts, Maine, Florida, New Hampshire, Maryland, and Minnesota, have implemented statewide zoning reforms. Although content and process vary considerably, these experiences offer valuable principles for effective state-level reform:

- Leadership Matters: In Montana, the Governor made clear that land use reform was going to happen, and then he brought in leaders from across the state into a Housing Task Force to identify needed reforms with a quick turnaround of only five months to produce a report. Governors in Colorado, Maryland, and Utah have similarly made housing reform centerpieces in their legislative agendas.

- Coalitions Matter: Successful land use reform requires government leaders engaging diverse stakeholders, including homebuilders, homeowners, tenant advocates, homelessness advocates, developers, environmental groups, transportation advocates, and local officials to identify common areas of interest. The executive branch needs the legislative branch, and state-level policy reforms work best when multiple groups can see their priorities reflected in them.

- Omnibus Bills Rarely Work but do Set the Stage: In the past few years, policymakers in several states have introduced wide-ranging omnibus bills that attempt to address all angles of the housing crisis. In general, these bills have failed. However, in the following legislative session, these omnibus bills often set the stage for numerous smaller bills that can get passed. This approach allows different legislators to support specific elements of what amounts to broader reform packages.

- Local Leaders Need a Voice at the Table: Rather than treating local leaders as obstacles, successful reform efforts engage them as essential implementation partners. Working with local governments and state municipal leagues can help ensure that state-level reforms can be implemented as intended, so long as local governments have the support that they need.

- Land Use Reform is Not a One-Shot Deal: Given the current regime of land use, permitting, and building code enforcement, changes are often iterative. While California first allowed Accessory Dwelling Units in the 1980s, there was little construction until state-wide reform in 2016 that reduced parking requirements and streamlined permitting. However, as localities found ways to circumvent the intention of the reforms, additional laws were passed in 2017, 2019, 2021, and 2022 — with more expected in 2025 — to allow for widespread ADU construction. The end result has been a striking increase in ADU permitting and construction, from fewer than 1,000 ADUs permitted annually before 2016, to over 20,000 permitted in 2021 alone.

Many of these best practices at the state level also apply to local level zoning reform:

- The Messenger Matters: Reform leadership should come from trusted community figures, whether the mayor, county executive, or council members. Communicating to the residents about the need for land use reform should come from trusted community leaders and needs to meet the community where they are.

- The Message Matters: Recent research from the Sightline Institute and Welcoming Neighbors Network emphasizes effective messaging strategies, including connecting housing shortages to competition and rising prices, highlighting how current community members are affected by the housing shortage, and clearly specifying the types of changes that would be introduced by land use reform.

- Coalition Building is Important: To enact land use reform at the local level may mean overcoming significant pushback from those who say, “Not in My Backyard” (NIMBYs). Successful campaigns to reform zoning codes have built coalitions of faith-based leaders, tenant advocates, homeowners, developers, homeless service providers, and more, who recognize that addressing the housing shortage means creating more homes in the community for those who already live there. Working with local grassroots coalitions to get to Yes in My Backyard (YIMBY) can mean that city councils, planning commissions, and mayors can point to clear, broad-based, public support — which we already know exists. Broadening the land use reforms city-wide, rather than focusing on only a specific set of neighborhoods, can make it clear that these reforms impact, and benefit, everyone in the community.

- Comprehensive Changes are Often Needed: Local zoning codes contains multiple, interconnected requirements affecting development and cost. In addition to limits on the number of units per parcel, cities must consider changes to a whole host of other requirements, including setbacks, minimum lot sizes, parking, lot splits, height requirements, floor area ratios, and more. Changing only the unit limits without these complementary changes can mean that, although more density is allowed by-right, these types of projects are still financially or technically infeasible.

- Land Use Reform Takes Time: Zoning establishes development parameters in a community. Development, however, takes time: homebuilders and developers need to internalize the changes to think differently about what they want to build; creating plans, securing financing, and building buildings also take time. While cities like Minneapolis show that zoning reforms can lead to decreased housing costs, it will take time for zoning changes to permeate through the housing development ecosystem, and is not indicative of zoning reform failure.

Local leaders across the U.S. have shown that zoning reform can succeed locally. The Othering and Belonging Institute has tracked over 150 local ordinances, general plan updates, and zoning code rewrites that promote more housing of all shapes and sizes in communities across the U.S.

Land Use, Permitting, & Building Code Reform

Thus far, zoning and land use reform successes have largely emerged from robust, grassroots mobilization advocating for increasing housing supply. This activism largely falls under the YIMBY (Yes in My Backyard) umbrella, with YIMBY organizations such as California YIMBY actively lobbying policymakers in state capitals and city halls. National organizations, such as YIMBY Action and the Welcoming Neighbors Network, have emerged to support state and local

chapters of “Abundant Housing” organizations. Nonprofits, such as the Mercatus Center, the Pew Charitable Trusts and The Center for Building in North America, have provided expertise and research to local and state policymakers in favor of zoning, building, and permitting reform.

The federal government has also taken steps to encourage zoning reform, with programs like HUD’s Pathways to Removing Obstacles to Housing (PRO Housing) program. Many jurisdictions that won PRO Housing grants did so with proposals that sought to modify zoning codes to allow for more housing. HUD also recently released a guidebook, Eliminating Zoning Barriers to Affordable Housing, which outlines eight land use reform types, and eight additional strategies, that municipalities can enact to encourage more housing development.

In Congress, many bills have been proposed to encourage zoning reform, such as the bipartisan YIMBY Act, which would require recipients of CDBG Block Grants to report on implementation of land use reforms, and the Reducing Regulatory Barriers to Housing Act, which would direct HUD to develop model ordinances and zoning codes, and provide technical assistance to cities to reform their land use regulations. The newly created YIMBY Caucus in the House of

Representatives signals a new, standing, coalition of pro-housing lawmakers.

In late 2024, a new organization, the Metropolitan Abundance Project, was launched by California YIMBY. Metropolitan Abundance aims to “provide a proven policy framework and work with leaders at the state and local levels to reverse” exclusionary policies and put cities on an abundance trajectory. In launching, Metropolitan Abundance provided six model state bills relating to: third party review, ADUs, housing on faith-based institution land, minimum lot sizes, off-street parking, and residential in commercial zones. These model bills are meant to be taken by state legislators across the country and proposed and enacted nationwide.

The National League of Cities, National Association of Counties, National Council of State Legislatures, and National Governors Association are all working with their members to promote best practices, case studies, and resources to promote land use, permitting, and building code reform. The National League of Cities recently launched its America’s Housing Comeback Advisory Group. These national membership organizations provide an important source of guidance and expertise to their members, the elected officials who ultimately must lead on the development and implementation of land use, permitting, and building code reform.

Land use, permitting, and building code reform have already begun successfully diffusing and scaling. To continue to amplify the diffusion and scaling of these initiatives would require the expanded and sustained support of organizations like Welcoming Neighbors Network — which currently counts 40 organizations across 24 states as their members. Welcoming Neighbors Network has spearheaded research on the language we use to talk about land use and zoning reform, to be used by policymakers and advocates through the country. As the housing crisis has grown from high-cost coastal regions to rural areas, the rust belt, and the heartland, more and more communities have recognized that land use, permitting processes, and building codes are often the first piece of the puzzle that needs to be solved by communities trying to build new housing to address their housing shortage and build more homes of all types.