"Right-Sizing" Property Tax Incentives to Increase Housing Affordability

AUTHORS: Michael Saadine, Andrew Gibbs, and Florian Schallol

Additional contributions from National Housing Crisis Task Force members: Susan Thomas, Josh Humphries, Rachel Diller, Laura Brunner, and Rebecca Foster

Key Points

- Property taxes often represent a significant operating expense for houses and apartments, and cities often have the power to lower property taxes for affordable housing.

- Tax abatements and exemptions present a trade off between lower revenues for the jurisdiction and increased housing production.

- Cities have developed tools to calculate this trade off and develop “right-sized” property tax incentives that balance the public and private benefits.

The national housing crisis manifests in many forms, but most impactful is the severe shortage of affordable housing units. In the absence of meaningful federal action in recent decades, and uncertainty regarding current federal priorities, state and local municipalities are increasingly taking action to build and preserve affordable housing.

Localities are deploying a wide range of tools and investments: tax abatements and exemptions, tax increment financing, payments in lieu of taxes, public land contributions, low-interest loans, voucher programs, and more. Most of these tools are effectively public subsidies to private developers or landlords, designed to incentivize the creation or preservation of affordable housing. Little analysis, however, has been done to understand 1) which tools make the most sense in which localities and housing developments, 2) how much these incentives are truly “worth” to developers, and 3) how much public entities should require in return (e.g., number of affordable units, level of affordability, duration).

The Challenge This Tool Solves

Often, existing incentive programs either provide excessive benefits to the private sector, generating insufficient social return for the cost, or offer inadequate incentives, resulting in no uptake and therefore no new affordable housing units. Such discovery is difficult for public entities that may not have robust financial underwriting teams and may distrust the analysis of the private developer, who is effectively sitting opposite them on the negotiating table. There is a need to bring a clearer understanding to the tradeoffs the public sector is making when offering incentives for affordability. While every locality is balancing different financial and policy variables, the underlying financial underwriting fundamentals remain relatively consistent. A select few localities have developed and refined financially sophisticated programs that generate affordability, offer the private sector sufficient incentives, and have guardrails against unfair deals.

Types of Communities That Could Use This Tool

Tax incentive programs are applicable across localities throughout the country. While specific mechanisms vary by location, the fundamental underwriting considerations remain consistent. Likewise, many communities across the country are suffering from shortages of quality, affordable housing, especially in income segments that are less covered by federal incentive programs. The proposed Underwriting Model offers geographic and income-level flexibility but could be especially effective in communities where political and fiscal conditions allow trading potential property tax revenue in favor of increased housing affordability.

Expected Impacts of This Tool

By highlighting best practices from across the country and providing a framework and shared language for the public and private sector’s understanding of project underwriting, we aim to help states and localities implement new tax incentive programs, strengthen public-private trust, and improve execution efficiency across both new and existing initiatives.

Most affordable housing in the U.S. is built by private developers. In this context, affordable housing refers to for-sale or rental housing with cost caps that make it accessible to moderate-and low-income households. Often, these caps result in prices below what would be financially viable based on development costs. To incentivize private developers to build affordable housing, the public sector must subsidize those costs.

There are many different subsidy programs in the U.S. for affordable housing. The largest, the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, subsidizes approximately 40–70% of the total development cost for rental housing, and caps the rents in the project to rents that are affordable to households earning 60% of the Area Median Income (AMI). Other federal subsidies for affordable housing include the HOME Investment Partnerships Program, Rental Assistance Demonstration Program, and USDA Section 515 Rural Rental Housing Loans, among others.

However, these federal incentives for affordability are limited, antiquated, overly competitive, and vulnerable to changing politics. State and local governments have stepped in with many of their own subsidies. These subsidies include direct grants and loans for specific projects, subsidized land, and abatements or exemptions on the property taxes that developments need to pay. This State and Local Housing Action Plan tool primarily focuses on property tax incentives, providing a framework for localities to compare the potential costs and benefits of subsidy programs, examining not only types of tax subsidies localities can provide but also the cost, “public return,” and, ultimately, the efficiency of those subsidies (i.e., units created or preserved and other public policy priorities served). We highlight examples of leading programs across the country, explaining the underwriting that makes them viable, and the tradeoffs considered in crafting them. We share a preliminary flexible underwriting model (the “Underwriting Model”) that can be used by the public and private sector as they consider implementing or using programs, and propose a much more robust, data-rich, open-source, and usable model to be built.

Property Tax Incentives for Affordability

The National Housing Crisis Task Force proposes that more localities implement property tax incentive programs to subsidize new and preserved affordable units. To support this expansion, we propose the creation of a flexible Underwriting Model paired with a standardized methodology to analyze and compare local incentive programs. This approach would establish a new set of standard metrics that account for differences in incentive structures and how they affect the various measures that are important to the public sector and to developers. Our initial proposed Underwriting Model is Excel-based and relies heavily on a number of assumptions that any given locality or developer would need to input. While this provides a foundation for understanding underwriting fundamentals, it serves primarily as a first step toward bridging the knowledge gap between developers and public entities regarding project finances and subsidy valuation. It is not intended to replace customized underwriting, and there remains the risk that local nuances may not be fully captured, or that developers may still have a different read of the project’s finances.

We envision a much more accessible and usable model as this project’s final output. A final model would be open-source, with standardized, dynamic, reliable data (such as rents, median incomes, and local tax rates) rather than relying on user assumptions. The model would be hosted online and accessible to anyone. Data sources would update constantly and automatically via API.

The proposed model would allow any public sector official or developer, almost anywhere in the country, to automatically evaluate a proposed incentive program. It would also guide users towards target key metrics. For instance, if the public sector knew it had a distinct need for mixed-income developments with a certain number of units at a moderate Area Median Income (AMI) level, the model might guide it to offer a partial tax abatement to achieve the metrics that would incent a developer to perform.

Production of the final online Underwriting Model will require additional budget to develop and a permanent home for hosting and updating. The National Housing Crisis Task Force’s initial Underwriting Model should serve as the testing ground for this more ambitious model.

A Background In Housing Finance

Understanding the basics of housing finance is essential to understand the value and tradeoffs of subsidies that localities can offer the private sector. While priority methodologies and inputs will always vary from place to place and developer to developer, the private real estate industry does adhere to some basic, consistent practices.

Revenues: Net Operating Income

Among the most important metrics underpinning real estate analysis is Net Operating Income (“NOI”). NOI is indicative of a project’s recurring revenues (e.g., rents) and is essentially calculated by summing rents and other revenues (e.g., parking) and subtracting typical operating expenses such as maintenance, utilities, insurance, and property taxes.

Revenues Compared to Costs: Yield on Cost

NOI, however, does not account for the substantial costs of developing or purchasing a property. To compare these costs to NOI, the real estate industry calculates “yield on cost.” To determine yield on cost, NOI is divided by total construction and / or acquisition costs. For example, a 7% yield on cost implies that a developer’s NOI will yield 7% on their total investment each year once the project is leased up.

Sale Price: Cap Rates

Capitalization rates or “cap rates” represent another important metric for project revenue. While NOI is an indicator of a project’s recurring revenues (e.g., rents), cap rates are an indicator of the property’s ongoing value and potential sale price. Cap rates represent, effectively, a desired yield for a stabilized project; in a traditional development environment, an investor should be willing to accept a lower yield once a project is built and leased because there are fewer risks related to construction delays or leasing the property. Cap rates are used to drive a proposed valuation or sale price. Like yield on cost, cap rates are a percentage yield metric representing NOI divided by valuation.

Putting it all Together: IRR

NOI, yield on cost, and cap rates all help determine the developer’s return on investment in a housing development. The most commonly used metric used to evaluate this return is called Internal Rate of Return (“IRR”). IRR is calculated by summing the cash flows (money spent or income received) each year. Generally, this consists of acquisition and development costs up front, less NOI while the project is leased out, and sale proceeds determined by the market Cap Rate at exit, also accounting for the impact of debt financing. These cash flows are then time-weighted to calculate IRR. These “leveraged” (including the effect of debt) Internal Rates of Return are targeted in the double digits for more stable assets and above 20% for the riskiest new developments.

Affordability has a distinct effect on these metrics. Rents are one of the most important components of NOI (and, as a result, on cap rates), and affordable housing units typically generate lower rents. If rents dip low enough, developers and investors may choose to walk away from a potential housing development. In exchange for lowering rents, the public sector can reduce operating costs (e.g., through a tax incentive like an exemption, abatement or tax increment financing (TIF)) to increase NOI or reduce development costs (e.g., through free land, grants or low interest loans) to lower the total cost denominator; either of these offsets can get the developer back to a market-rate yield on cost. While every project has dozens of moving pieces, understanding precisely how these incentives affect a developer’s finances is critical to understand which incentives to provide, and how deep they should be for maximum effect.

As state and local governments assume greater responsibility for affordable housing production and preservation, innovative tax incentive programs have emerged nationwide. The following examples highlight effective approaches from Texas, Atlanta, and Chattanooga.

Case Study

Texas’s Public Facility Corporations

"Right-Sizing" Property Tax Incentives to Increase Housing Affordability

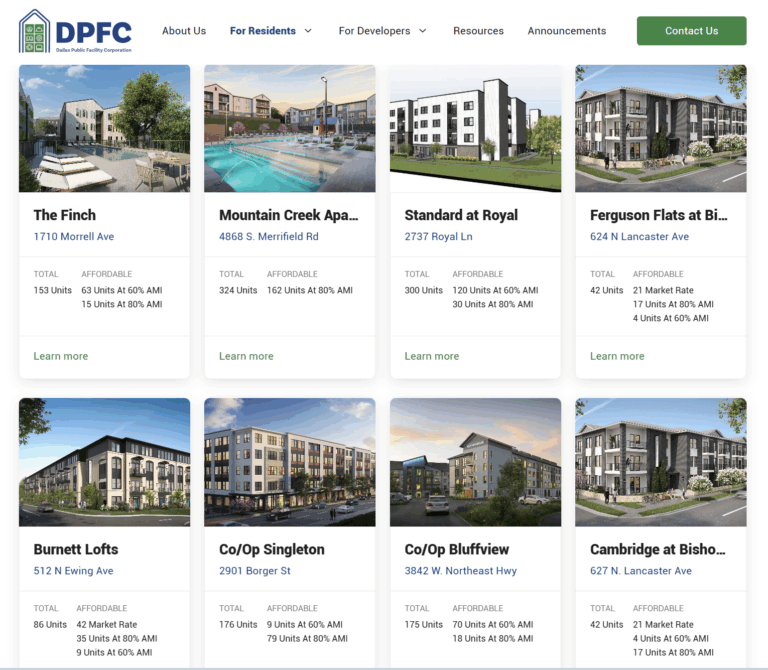

In 2015, Texas implemented a unique multifamily tax exemption program. Facilitated under Texas Local Government Code, Texas is one of the first places to provide this form of incentive to create affordable housing and, as a result, it has had opportunities to refine the program towards ensuring it accomplishes its intended public purpose over time.

Read More About Texas’s Public Facility Corporations

Case Study

Atlanta’s Private Enterprise Agreement

"Right-Sizing" Property Tax Incentives to Increase Housing Affordability

In 2023, as part of Mayor Dickens’s pledge to create 20,000 affordable housing units, Atlanta established the Atlanta Urban Development Corporation (“AUDC”). Beyond functioning as a “European style” public developer, AUDC created a program leveraging the Private Enterprise Agreement (PEA), found in the original 1937 Georgia Housing Authorities Law, to provide tax exemptions to projects that provide a minimum number of affordable units.

Read More About Atlanta’s Private Enterprise Agreement

Case Study

Chattanooga’s PILOT Program

"Right-Sizing" Property Tax Incentives to Increase Housing Affordability

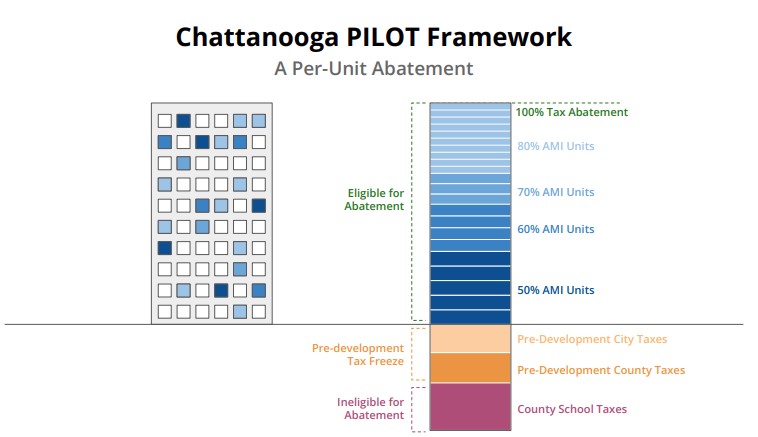

Chattanooga recently instituted a Payment in Lieu of Taxes (PILOT) program to offer developers a 15-year tax abatement commensurate to the number of affordable units created. Similar to Atlanta and Texas, the PILOT is enacted through a ground lease between a public entity, the Health Education and Housing Facilities Board, and a private or nonprofit real estate operator.

Read More About Chattanooga’s PILOT ProgramDiffusing and Scaling Property Tax Incentives for Affordability

Defining and Prioritizing

With the myriad incentive structures in Chattanooga, Atlanta, Texas, and beyond, combined with the long slate of variables involved in each individual project, it has historically been difficult to assess the structure and value of one affordability program to another. As local programs grow more urgent and prevalent, it has never been as important to create such a tool and methodology.

We propose a methodology of comparing local tax incentive programs via standardized metrics that account for effects on key private underwriting metrics, including net operating income (NOI), yield on cost, cap rates, and internal rate of return (IRR). In modeling the balance of costs and benefits of affordability programs, we focus on three key additional metrics: Public Return on Investment, Friction Costs, and Private Internal Rate of Return Enhancement.

Public Return on Investment (PRI) compares public benefits (often in the form of reduced rent) to public costs (often in the form of lost tax revenue via a tax incentive). These costs and benefits should be time-weighted to account for the time value of money and calculated as a net present value:

PRI: First, the net present value of all the rent savings (from the affordable units) is calculated. This sum is then divided by the net present value of all of the reduced taxes from the tax abatement. Net present value is a methodology that discounts future cash flows into “today’s” dollars.

In a market environment in which development deals do not pencil (returns are below equity cost of capital) and / or affordability is optional, we would expect the PRI to be less than 1x (present value of subsidy is greater than public benefit). In an efficient market, the extent of this gap should be smaller. Due to changing market conditions, it can be challenging to estimate an exact “correct” ratio.

Friction Costs (FC) represent the difference between the value of the subsidy provided (e.g., taxes foregone) and the value received by the developer. For example, subsidies that often require help from specialist consultants and / or need additional high-cost financing can lead to significant incremental costs outside of a project’s true development costs. This metric can help local government leaders determine the most efficient allocation of public resources. For tax incentives, friction costs can be grouped into two costs: 1) legal and closing costs associated with obtaining the incentive; and 2) annual administrative costs for monitoring compliance with incentive mandates. There are also potential friction costs that are harder to quantify, including a developer’s level of comfort and familiarity engaging in what may be a more complex transaction; colloquially the “is it worth the headache?” cost.

FC: Calculated by taking the sum of up front Legal Costs, the net present value of Annual Compliance Costs, and (if quantifiable) an estimate for additional resources needed to handle the “headache” of a more complex transaction. That sum is divided by the net present value of total Estimated Reduction in Rents. FC is calculated as a percentage, with FC below approximately 5% considered to be relatively efficient, especially as compared to commonly used federal programs.

Private Internal Rate of Return Enhancement (PIRRE) measures the incremental benefit to private developers of every public subsidy offered for various affordability options. It is calculated by taking the net change in IRR to a developer as a result of the affordability program. Different tools can have very different effects: for example, cities may spend years setting up belowmarket interest loan funds while a property tax abatement could have had quicker and more efficient impact on enhancing IRR. When calculating the incremental IRR for enhancement, it is important to include the effect of Friction Costs.

The analysis also considers potential valuation impacts from increased cap rates due to buyers’ perceptions that restricted rents may lag market growth over time. Based on conventional underwriting methodologies, cap rate adjustments (and resulting valuation effects) typically reflect the differential between NOI growth with and without affordability restrictions, though this varies significantly by market. This effect on exit valuation is factored into the calculation of IRR.

PIRRE: Calculated by taking the difference between the private investor’s net IRR after the tax abatement and the private investor’s original IRR before the tax abatement.

PIRRE is calculated in percentage points (%pt). While the absolute PIRRE matters (a higher number means a higher incentive for developers), it is typically more important that the gross IRR reaches developers’ minimum return thresholds (this number will vary based on the investor’s targets and comfort with risk; under current market conditions, the mid-tohigh-teens might justify proceeding with a project).

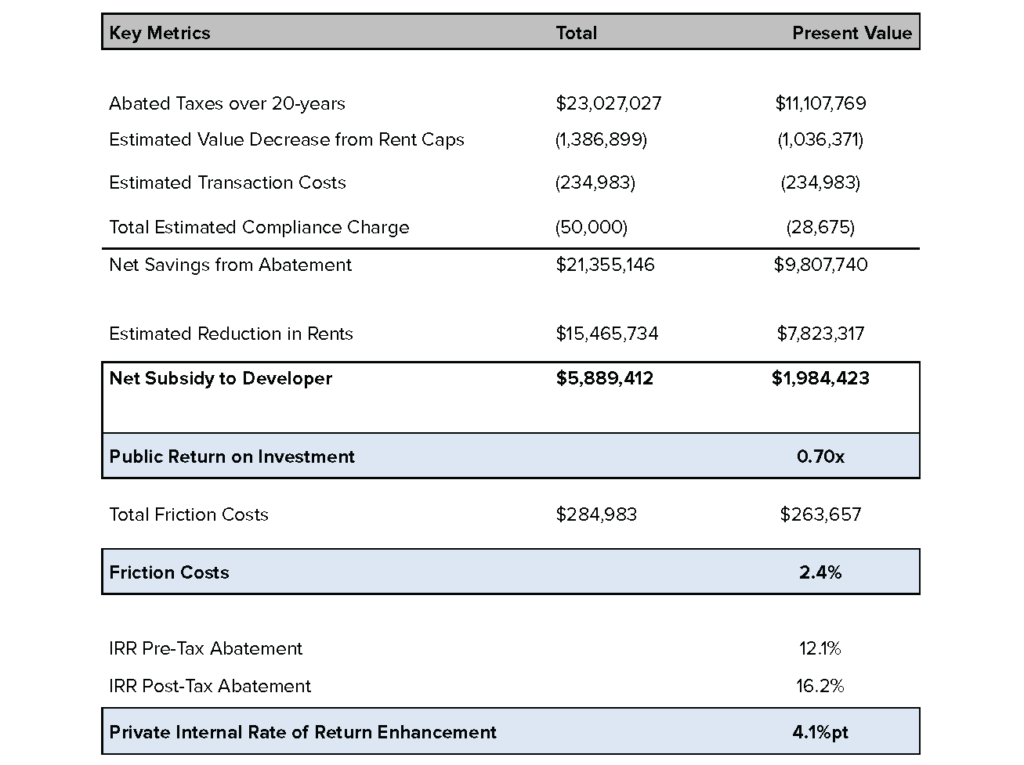

Model Example: Full Tax Exemption for Mixed-Income Housing

Below highlights key metrics based on utilizing a hypothetical tax abatement for a development project of 200 units. We assume the program offers a full property tax exemption in exchange for 20% of units being held at 50% of AMI, and 10% of units being held at 80% of AMI. All metrics are hypothetical and reliant on several key assumptions regarding the geography and property’s rents, property taxes per unit, and cap rates. With those assumptions entered, the model boils down to consideration of the key metrics we propose standardizing.

The ~$8 million of present value of reduced rents compares to ~$11 million of present value of abated taxes, resulting in a Public Return on Investment of 0.7x. By being relatively close to 1x, this demonstrates a net benefit to the developer without being overly generous — perhaps just enough sacrifice to make a project and its corresponding new affordable units and economic development viable. Friction costs are minimal, at ~2%, representing significantly more efficiency than many other affordable housing programs. Finally, the project’s IRR goes from 12.1% without the program to 16.2% with it. This demonstrates that the benefits to the developer could be sufficient to move this particular project from a likely unviable returns range to one that may convince investors and lenders to pursue it.

The Public Return on Investment is not too severe, the Friction Costs are minimal, and the Private IRR Enhancement is material, meaning this incentive program would likely result in a previously unviable project being executed — producing net new affordable housing units.

Introduction to the National Housing Crisis Task Force’s Model

Using the metrics and early methodology outlined above, the National Housing Crisis Task Force proposes building a standardized Underwriting Model that calculates the public and private costs, as well as the public and private benefits, of local affordability incentive programs. The model would standardize some key metrics in the context of tax incentive programs, such as Public Return on Investment, Friction Costs, and Private Internal Rate of Return Enhancement to compare real and hypothetical incentive programs. In doing so, the model will help localities efficiently structure incentives and maximize the number of affordable housing units built or preserved in their localities. Our proposed model focuses on accounting for the complexity of all input variables while also generating a neat, digestible output of standardized metrics.

Key standard modeling inputs include the project’s parameters, including number of units, unit types, proposed level of affordability, and size; rent levels, both market rate and affordable, and vacancy estimates; operating costs, including repairs and maintenance, marketing, utilities, insurance, and property taxes; development costs, including land value, hard costs, developer fees, and soft costs; financing assumptions, including senior and mezzanine debt levels and interest rates, and exit assumptions, including hold period and driven primarily by exit cap rate and transaction costs.

The public’s contribution assumptions are also accounted for via affordable rent levels, tax incentives, grants per affordable unit, below-market debt, free land, and project-based voucher rents.

These inputs generate net cash flows which generate an Internal Rate of Return for the project, with and without the incentive program in-place. All parties involved can easily compare a pure market-rate project to one that achieves the locality’s affordable housing goals, bridging the gap between what a private developer asks for and what a public entity can offer.

The initial model is under production in spreadsheet format, and with additional funding, the Task Force anticipates building out a more sophisticated web-interface model on an open platform for use by state and local leaders.

Diffusion and Scaling Via Standardized Modeling

The market writ large, and Task Force Members’ experience specifically, highlights myriad situations in which distrust or misunderstanding of key metrics was the bottleneck to the execution of compelling public-private developments. We propose that pursuing a dynamic, user-friendly model focused on property tax incentives will help close the gap between the public sector’s needs and private developers’ requests. By providing an open-source, objective analytical framework, the proposed model could reduce friction and unlock the scaling of some of the local “best practice” tax incentives that have sprung up around the country.

State and local government leaders interested in supporting the Underwriting Model’s development or testing the initial Excel model should contact the National Housing Crisis Task Force at info@nationalhousingcrisis.org. As we work to refine the tool, build our database, and develop market norms, we greatly value and welcome collaborating with localities to understand how their programs align with our proposed standardized metrics.